Hirst, 2014 GQ cover

A few weeks ago I attended a pretty great lecture about copyright issues artists often face. I kind of forgot about it until I did that post on the YBAs and found out a lot more about Hirst and the suspicions of idea stealing casting shade on his work, reminding me of the copyright lecture. So I decided to investigate a little further into these claims, since it was too much of a coincidence to ignore.

But first a quick summary of Hirst’s rise to stardom:

Damien Steven Hirst (born in Bristol on June 7, 1965) has managed to stand out among his YBA peers by becoming a savvy entrepreneur marketing his art. He was first inspired by Francis Davison after seeing his exhibit at the Hayward Gallery in staged by Julian Spalding in 1983. Davison made abstract collages from torn and cut coloured paper to which Hirst responded with “blew me away.” Well Hirst was so blown away that for the next two years he claims he modeled his own work after Davidson’s collages. Hirst was then admitted to Fine Art at Goldsmiths, University of London in 1986, after two attempts, where he studied through 1989. In school Hirst was again inspired, this time by Micheal Craig-Martin when he saw his senior tutor’s piece An Oak Tree.

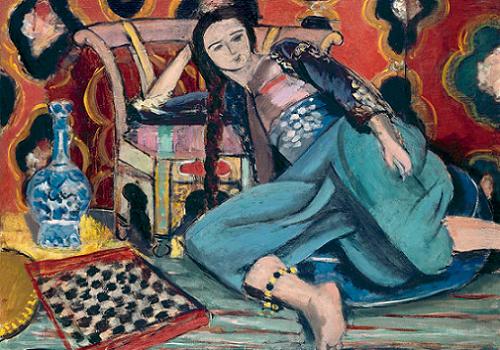

But Hirst’s art really got attention when death became his focus, providing finally the platform for his great success, and his chance to outshine the rest of the YBAs. While a student, Hirst was placed at a mortuary, and it was most likely this experience that compelled him to explore the theme of death and internal structures of the body in his most well-known works. His art features an menagerie’s worth of animals, dead and often dissected, preserved in formaldehyde. Probably the most familiar of these is a 14-foot (4.3 m) tiger shark immersed in formaldehyde in a large vitrine (clear display case) titled The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living. Hirst also made “spin paintings,” created on a round, rotating surface, and “spot paintings”, which are rows of randomly coloured circles created by his assistants.He is internationally recognized as the richest UK artist. Some compare him to Jasper Johns and Jeff Koons in his ability to command huge prices for his works.

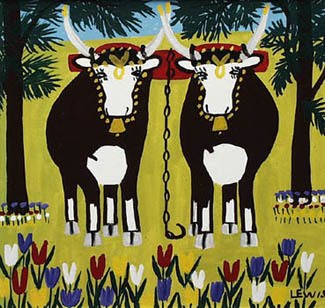

Hirst continued to do well by selling prints and accessories bearing his signature styles and images through his company, Other Criteria which he co-founded in 2005. But his biggest cash-in took place in Septemeber 2008 at Sotheby’s, London, where Hirst took an unconventional tactic in art exhibiting and auctioned his work directly to the public; by-passing his usual galleries. This two day auction, called “Beautiful Inside My Head Forever,” exceeded all predictions and brought in roughly $198 million for 218 items. He broke his own sale record with £10.3 million for The Golden Calf (an animal with 18-carat gold horns and hooves, preserved in formaldehyde) as well as the record for a one-artist auction— by ten fold! Hirst was undoubtedly pleased, though according to the Independent the artist was not on board with the idea at first and had to be convinced by his business advisor.

Hirst, from his Butterfly Paintings

But his rapid accumulation of wealth and prominence did not shield him from critical attacks questioning his authenticity. Since 1999, Hirst has been called a plagiarizer in articles by journalists and artists. In 2010, Charles Johnson described in The Jackdaw 15 cases accusing Hirst of plagiarizing other work. Examples included Joseph Cornell’s claim that Hirst’s Pharmacy was a copy of a pice he made in 1943; Lori Precious who had made stained-glass window effects from butterfly wings from 1994 several years before Hirst; and John LeKay who did a crucified sheep in 1987. A spokesperson for Hirst said Charles Johnson’s article was “poor journalism” and that Hirst would be making a “comprehensive” rebuttal of the claim.

But many other critics point out that Hirst’s spin paintings and installations, particularly one of a ball on a jet of air, are barely altered versions of pieces made in the 1960s, hardly original. And the accusations just kept on coming.

Chef Marco Pierre White said Hirst stole from his Rising Sun, on display in the restaurant Quo Vadis, to make Butterflies on Mars. In 2000, Hirst was sued for breach of copyright over his sculpture, Hymn, which was a 20-foot (6.1 m), six ton, enlargement of his son Connor’s 14″ Young Scientist Anatomy Set, designed by Norman Emms, 10,000 of which are sold a year by Hull-based toy manufacturer Humbrol for £14.99 each. Hirst was forced through legal proceedings to prove his authorship which led to an out-of-court settlement requiring him to pay an undisclosed sum to two charities, Children Nationwide and the Toy Trust as well as a “good will payment” to Emms. This “charitable donation” was much less than what Emms hoped for, but Hirst also agreed to restrictions on further reproductions of his sculpture.

In 2006, Robert Dixon, a graphic artist, former research associate at the Royal College of Art and author of ‘Mathographics’, alleged that Hirst’s print Valium had “unmistakable similarities” to a design from his book. Hirst’s manager contested but his refutal did more damage than good. This explanation was that the origin of Hirst’s piece came from the book The Penguin Dictionary of Curious and Interesting Geometry (1991) not realizing this was one place where Dixon’s design had been published.

In 2007, artist John LeKay again accused Hirst of stealing his ideas, but this time asked only that Hirst acknowledge his him as an effluence. LeKay said he was once a friend of Damien Hirst between 1992 and 1994 and had given him a “marked-up duplicate copy” of a Carolina Biological Supply Company catalogue, adding “You have

Hirst, “For the Love of God”

no idea how much he got from this catalogue. The Cow Divided is on page 647 – it is a model of a cow divided down the centre, like his piece.” This refers to Hirst’s work Mother and Child, Divided—a cow and calf cut in half and placed in formaldehyde. LeKay’s goes on to say Hirst copied the idea of For the Love of God from a crystal skull he made in 1993, and pleaded for credit for his work saying, “I would like for Damien to acknowledge that ‘John really did inspire the skull and influenced my work a lot.'” Hirst’s copyright lawyer Paul Tackaberry reviewed images of LeKay’s and Hirst’s work and saw no basis for copyright infringement claims in a legal sense, but it does make one wonder about the legitimacy of LeKay’s accusation and the rest of the allegations charging Hirst of plagiarizing. It seems that Hirst built a career in art making by not only sage marketing and promoting strategies (the man was undeniably an innovative entrepreneur) but also by deftly navigating the thin space between appropriation and stealing.

Finally, Jim Starr’s upheaval over Hirst’s GQ cover shot of Rihanna as the snaked-headed monster Medusa is the most recent blow to his authorship. Starr claims to have been the first to “portray the sexy snake-haired woman.” But I take issue with Starr on this one. By now Hirst has become an easy target, but Starr has little backing to his charge since there is an entire cannon of images of Medusa that outdate both Hirst and Starr. I suspect plagiarism claims are redundant when artists have been depicting something for more than 2,500 years. She was a popular icon through out Greece and even Carvaggio was inspired by her snaky charm enough to make her an unlikely icon of baroque art in the 17th century. In fact, Carvaggio’s Medusa, a “portrait” of the monster painted on a shield, is one of the most incisive images of myth ever created. So in this instance I will charge Hirst, and Starr as well, of being guilty of creating dull art, ordinary, uninspired, and redundant of better works.

.jpg)